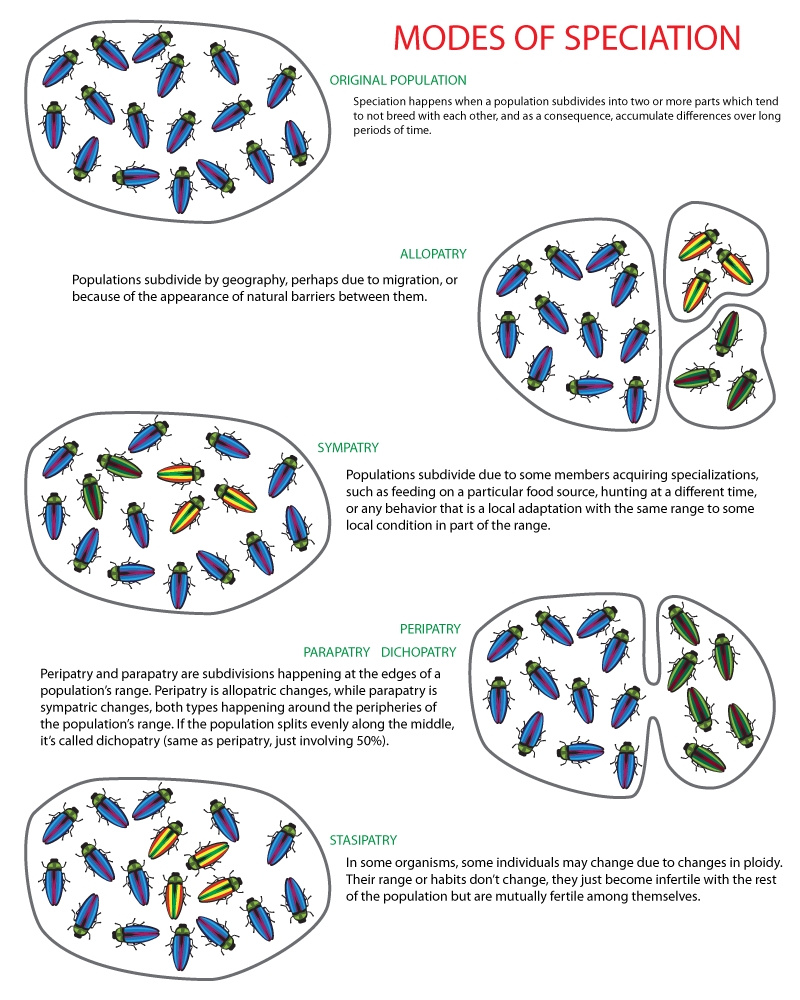

There are several terms that describe how speciation occurs. All species arise from pre-existing species through a process of reproductive isolation. A number of individuals break off or subdivide from a population, and become reproductively isolated. They breed among themselves, but not with the rest of the population. Over time, differences accumulate, but these differences remain within the break-off group and are not transmitted to the rest of the population because of the breeding barrier. Similarly, differences develop in the larger population after the split, which are not transmitted to the break-off group because of the same breeding barrier. These differences eventually become significant enough to make cross-breeding impossible between the groups, even if it had been initially possible. The break-off group then become a new species.

The chart below shows some common ways in which this can happen.

Allopatry

This happens when there is a geographical barrier between the subpopulation and the main population. A barrier can appear as a result of migration, for example, if a number of individuals migrate to a different location and there is a separation of many miles between them and the original population. Or it can happen when natural barriers appear, which subdivide the population. For example, a dry area of desert may appear in the middle of a population, separating it into two, a river might appear in the middle of a range. Or continents may split apart. Although such things can take some time (a few thousand years), in terms of the lifespan of a species, they are brief and rapid events. Typically, changes will happen much faster in the smaller subdivision, because of genetic drift and the founder effect.

Sympatry

This happens in populations that are not separated by what we typically understand as a "geographical barrier". An example might be that a forest contains a patch of trees of a certain species, for unrelated reasons (perhaps it's a clonal growth, could be any number of reasons). A leaf-eating population of insects inhabiting that forest become subdivided because certain members of that population exist in that patch of trees, and therefore only eat from its leaves. Over time, they may become specialized and prefer leaves from only those trees, even if other trees later become available. Such small changes can start a trend which becomes magnified over time. For example, these trees might come into flower at a specific time of the year, different from other trees around them. This will over time affect the lifestyle of the insects specialized to eat from them, perhaps changing their mating time to coincide with the flowering of their chief food source. They may thus not mate with the larger population even when they can, because their mating cycles have become desynchronized with the larger population.

Peripatry and Parapatry

These are similar to allopatry and sympatry, respectively. Peripatry is like allopatry in that there is geographical isolation, but there is no geographic barrier as such. Instead, it happens along the periphery (hence peri-patry) of the population's range. Typically, population density is greater near the center and drops off towards the periphery. So gene flow might be very high among parts of the population near the center, but quite low at the periphery. In such cases, differences may develop between subpopulations at the center and at the periphery, leading to eventual speciation.

Parapatry is more like sympatry in that the original cause for the subdivision of the population is not geographical, but rather behavioral. Again, it may be a specialized food source which forces different foraging behaviors, different mating behaviors. However, this happens on the edge of range, not anywhere in the middle like for sympatry. The result is that the thin population density at the edge soon causes individuals to either adopt the new lifestyle or retreat to the main population, if they want to continue to mate. So a geographical isolation appears (again, in the absence of typical geographical barriers), but here the isolation begins with changes in behavior. Unlike peripatry, where isolation appears first, and then behavioral and genetic differences.

Dichopatry

This is sort of a catchall term that could apply to any kind of -patry, the difference being that the population is divided evenly into approximately equal halves. This is a special case, because normally the main population is much larger than any break-off group. It has relevance for speciation, in that genetic drift is slow in large populations, therefore the two subpopulations will drift apart very slowly.

Stasipatry

This happens in a limited number of species (some plants, some grasshoppers). Due to errors in reproduction, some individuals may have different ploidy than the main population from which they derive - that is, they may have double or triple the number of chromosomes. In many species, such a situation would kill the individuals containing these errors, or at least make them sterile. However, in some species, these individuals live, and while they are infertile with the main population, they are fertile with other individuals who have the same ploidy error. They can then mate and give rise to a subpopulation which can be exactly like the parent population in morphology or behavior, but are reproductively isolated from it.